The Power of Film Scores

Several years ago, when my interest in cameras started replacing my interest in slacklines, a little dream began to grow in me, of one day having an orchestra record an original film score.

I grew up with classical music and remember well, how those high, penetrating clarinet tones floated through my home, accompanying my childhood almost daily. For me, there is no deeper and more complex way of feeling emotion, of mobilizing strength and energy, than listening to a classical orchestra. Music tells a thousand and one stories: it can speak of deep sadness and infinite loneliness, be movingly happy and shimmering in green hues of hopefulness, but also be mean and bitterly accusatory. When I listen to music I live and feel meaning, despite all other insecurities. What would life be without music? Probably more desolate, and probably full of silent films.

Music underlines images or lifts them up. But music can also be contradictory and knowingly cynical; it can slyly speak of the exact opposite of what is being shown. Connecting images with music is probably the most difficult and demanding terrain in the long marathon of film production. What is needed for a great film score is a master of the trade: a music composer with years of experience. I had the great luck of coincidentally meeting one.

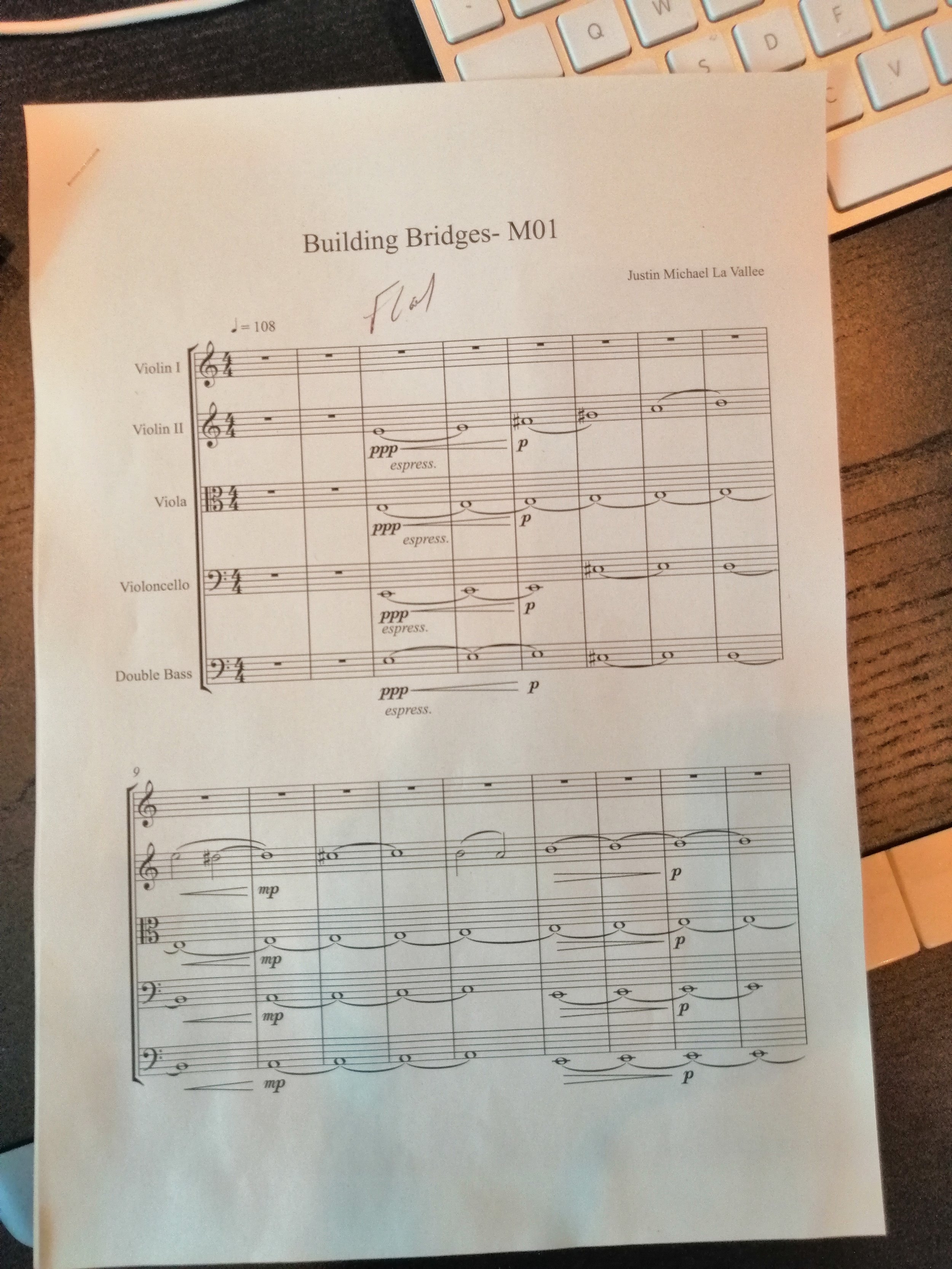

Justin La Vallee grew up in Manhattan and attended the “Manhattan School of Music”. In 2010, he wrote the score for the film “Inuk”, which was nominated in the category “Best Foreign Film” at the 85th Academy Awards. I met Justin in Austin and we immediately hit it off. He is an extremely talented musician and our partnership is the very picture of German-American friendship and cooperation in action.

Justin’s studio is located in Berlin, in the district Friedrichshain, and his company – Q Music and Sound Couture – is one of the top addresses for film music in Germany. Q Music has a very good relationship with the Hungarian Film Orchestra and was able to negotiate a very good deal for us. The score for BuildingBridges was not conceived as a purely classical one, it was to contain Americano- and electronic elements. A so-called hybrid – a genre established years ago by Hans Zimmer.

I had to entrust the entire musical accompaniment to Justin. Usually I like to keep control over all aspects and I find it hard to just let others do their thing, so this was a big step. Justin told me later, after completion of the project, that he had heard the melody of the strings at our first meeting in Austin and that thusly, the foundation of the music had already been cemented back in America.

From the very first note, the soundtrack had the task of making it clear to the viewer where the film takes place: in America’s Wild West. For this, Justin used soft Americano-sounds that he recorded with an electric guitar. Overall the music should not be quiet, but loud, a crescendo. The main target audience of the film is Americans, whose films, be it in their acting, their dialogues, or their music, are known to be bigger and louder.

In total I was in Berlin three times. I missed my train back to Munich twice because I couldn’t get myself to leave the studio. The last evening before the mastering was the most exciting of all. Tobias Wagner, who worked on the project alongside Justin, had the ingenious idea of inviting his girlfriend, the singer Glacéia Adele Henderson who sings mezzo-soprano in the “Vivid Grand Show”, to enrich our film with her wonderful voice. The session lasted until 2 AM and I remember vividly my feelings, walking though nighttime Berlin.

I crossed the Spree at Berlin’s East train station and was drunk with happiness. On the narrow sidewalks of the train station some wild Berlin party people were walking about and the bridge, with its scenic views, enticed me to stay and observe for a while. I was standing with my back to the railing and was listening for the hundredth time to the recording of the orchestra that had been made two days earlier. Paired with the still fresh impressions of Glacéia’s voice, I could finally see a picture emerge of what the final film would look like. For the first time, I had the feeling that we had made something sensible and that the film could work. I was proud to know, that the strings in our score hadn’t just been pulled out of some music catalogue, but had emerged from the whirring air of real violins and violas. From an orchestra.